Cameroon’s future between fragility and change after Biya’s eighth-term victory

Amid rising protests across Cameroon, the National Vote Counting Commission announced that President Paul Biya had secured another term with 53.66% of the votes, ahead of opposition rival Issa Tchiroma Bakary, who received 35.19%, according to official results. However, the Cameroonian public did not receive these results quietly. Cities in the north witnessed clashes between security forces and opposition supporters who viewed the electoral process as a continuation of political exclusion.

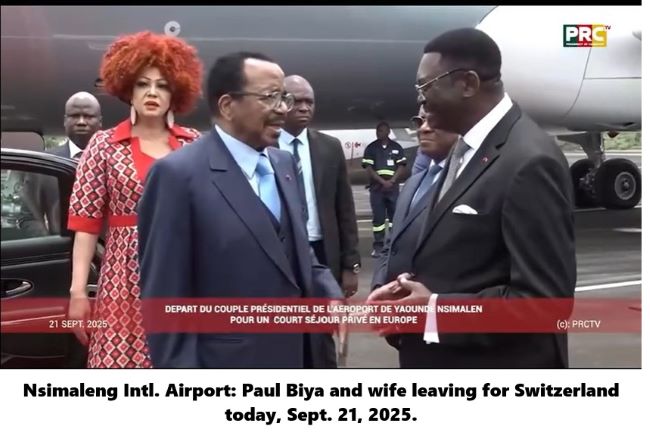

Internet shutdowns, rejection of appeals before the Constitutional Council, and conflicting reports about voter turnout signaled escalating political and social tensions. With 92-year-old Biya declaring victory for an eighth term, Cameroon entered a highly sensitive phase defined primarily by questions of legitimacy and the regime’s capacity to manage public anger.

The recent election transcended a mere political contest; it became a test of the regime’s ability to renew itself amid eroding public trust and mounting security and economic challenges. Between a president who has clung to power for over four decades and an opposition struggling to gain a foothold, an underlying crisis emerged—one extending beyond the ballot box to the very structure of the state. Disputes over the results and the regime’s attempts to reach political settlements by co-opting select opposition figures reveal an acute awareness of the moment’s gravity. Cameroon now faces not just an electoral crisis but a pivotal juncture that will determine whether it can renew its political system or sink into chronic tension and paralysis.

This analysis sheds light on Cameroon’s future following its disputed presidential elections by examining the current political and economic landscape and forecasting the challenges likely to arise under President Biya’s continued rule amid growing demands for change.

Features of the Electoral Landscape

Cameroon’s presidential elections unfolded within a political scene largely predetermined by the dominance of the ruling Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM), which has controlled state institutions for over four decades. The electoral process resembled a renewal of allegiance to the existing regime rather than genuine democratic competition. The opposition faced security and legal restrictions that crippled its ability to mobilize or organize supporters. Prominent opposition figures such as Maurice Kamto were placed under tight surveillance, while smaller parties suffered from administrative and media constraints. This closed electoral environment reflected a clear decline in political pluralism, reproducing a pattern that has defined Cameroonian politics for decades: elections serve to consolidate power rather than renew it.

Key features of this landscape include:

1- Dominance of the ruling party and decline of the opposition: The CPDM’s continued hegemony characterizes the political scene. The party maintains control of state institutions, supported by constitutional amendments abolishing presidential term limits, which renders electoral competition largely symbolic as the opposition is legally and security-wise confined, preventing meaningful public engagement. Political pluralism weakens, and elections function as mechanisms for regime renewal rather than power alternation.

2- Security tensions in separatist regions: The northwest and southwest regions remain mired in chronic instability due to armed conflict with English-speaking separatists. The war, ongoing since 2017, has left thousands dead and hundreds of thousands displaced, undermining national dialogue efforts, threatening electoral integrity, and restricting popular participation, as large segments of the population are prevented from voting while chaos is exploited to tighten security control at the expense of political openness.

3- Erosion of public trust in the electoral process: Cameroonians have lost faith in election integrity after a long history of politicized institutions. Since constitutional limits were lifted in 2008, elections have become tools for perpetuating power. Repeated postponements of parliamentary and local elections deepen doubts about the regime’s intentions. A general sense of frustration prevails, especially among youth who increasingly view the political process as a closed system incapable of delivering real change.

4- Economic pressures and rising cost of living: Despite modest economic growth, Cameroon faces a severe livelihood crisis. Poverty and youth unemployment worsen, inflation persists, and prices of basic goods continue to rise. These conditions generate widespread discontent that weakens government credibility, while economic rhetoric in election campaigns serves mainly as propaganda rather than a platform for genuine reform addressing the socioeconomic crisis’s roots.

5- Role of youth and digital media in politics: Despite restrictions, youth and digital media have become active political players. Online platforms have evolved into spaces for debate, mobilization, and abuse monitoring, disrupting the regime’s monopoly over traditional media. Yet repression and arrests limit their effectiveness, leaving the digital youth movement energetic but unable to translate online influence into tangible political change.

6- International monitoring and fears of fraud: Concerns about electoral manipulation persist amid weak independent oversight. The African Union and European Union have called for transparency guarantees, while the government rejects foreign involvement.External influences intersect: France maintains traditional support for the government, while Russia expands its media footprint, undermining electoral legitimacy and transforming the process into a stage for geopolitical contention rather than authentic democratic practice.

7- Stalemated reform and enduring political paralysis: The political landscape remains blocked. Reforms are limited to symbolic promises without substantive implementation. State institutions remain subordinate to the regime; civil society is constrained; the judiciary lacks independence. With no political will for change and public trust in decline, future elections appear as mere repetitions of the past, perpetuating political stagnation and postponing any prospect of real democratic transition.

Internal Divisions

Following the presidential results, Cameroon witnessed an unprecedented wave of violence spreading from the north to the capital, Yaoundé, as protests erupted over what the opposition called massive electoral fraud. Security forces confronted demonstrators with force in cities such as Garoua and Maroua, leaving several dead and dozens arrested.

A near-total internet shutdown, confirmed by NetBlocks, appeared as an attempt to control information flow and suppress images of repression. The digital blackout reflected the regime’s fear of a public explosion of anger and revealed that the state continues to treat the crisis as a security threat rather than a political legitimacy issue—deepening the chasm of distrust between rulers and society.

The opposition refused to recognize Biya’s victory, denouncing the election as rigged and calling supporters to protest in rejection of the results. Demonstrations quickly escalated into bloody confrontations, resulting in deaths and injuries amid intense repression and mass arrests of opposition leaders and activists, including prominent figures backing candidate Issa Tchiroma, reflecting the fragility of Cameroon’s political landscape and the growing likelihood of deeper crisis as authorities persist in choosing coercive security measures over genuine dialogue.

Earlier, opposition candidate Issa Tchiroma Bakary declared himself the legitimate winner, openly challenging the regime and accusing the Constitutional Council of complicity in “defrauding the nation’s will.” The ruling party dismissed his declaration as “political deception,” but the move marked a sharp escalation exposing the electoral system’s weakness.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Church, through the National Episcopal Conference of Cameroon (NECC), called for calm and respect for the people’s will, asserting that “truth and justice are the foundations of peace.” The Church’s involvement, though not new, carried an unmistakably political tone this time. Its firm stance reflected growing loss of confidence among religious elites in the regime’s neutrality and served as an implicit warning against the country’s potential descent into deeper violence.

Domestic reactions to the election results revealed a deep fracture within Cameroon’s political and social fabric. Between an opposition accusing the regime of usurping power and a government justifying its iron grip in the name of stability, the voice of the street is lost amid fear and disillusionment. Official institutions such as the Constitutional Council and the Ministry of the Interior adopted a defensive discourse centered on “the dignity of the state,” while civil and religious elites attempted, unsuccessfully, to contain the crisis. This turbulent dynamic underscores how elections have ceased to be democratic exercises and instead become a national crisis of legitimacy—where the problem lies not only in the results but in a governance system refusing to acknowledge the necessity of change.

Compound Challenges

President Paul Biya faces a deeply unsettled domestic landscape where economic crises intersect with political divisions and security threats. Limited growth has failed to improve living conditions, institutions suffer from eroding legitimacy, and conflicts on the peripheries continue to drain state resources while weakening stability. The situation is further complicated by the absence of a clear vision for power transfer and growing polarization between the ruling elite and the public, amid a bureaucracy weighed down by corruption and administrative paralysis in vital areas such as voter registration and election management. External pressures—both financial and media-related—also constrain the regime’s maneuvering room, and this intricate combination of internal and external strains makes Biya’s new term a decisive test of his ability to restore state balance.

First- Economic challenges:

1- Rising poverty rates: Although growth estimates hover around 4%, this has not translated into better living conditions. About 40% of the population remains below the poverty line. Turning growth into real opportunity requires tax reform, expansion of social safety nets, and redirecting investment toward neglected northern and western regions instead of focusing solely on showcase projects.

2- Rising unemployment: Youth unemployment leads to irregular migration or recruitment into armed groups. The presidency faces a major test in linking vocational training to local value chains—agriculture, processing, and logistics—while simplifying licensing and tax procedures for startups and encouraging private investment in the digital economy. Real pathways for integration require such measures rather than short-term electoral promises.

3- Financial corruption and administrative fragility: Cameroon suffers from widespread bribery and weak governance. Implementing digital systems, ensuring oversight body independence, and linking ministerial performance to public indicators are necessary. Without these reforms, the trust deficit will deter investment, while inflationary pressures and commodity fluctuations strain the national budget.

Second- Political challenges:

1- Erosion of legitimacy and institutional strain: Disputed election results and repeated postponements fuel growing public tensions. Biya faces a crisis of internal legitimacy unless he initiates genuine political opening—expanding participation, bringing in new figures, and fostering inclusive representation to ease polarization.

2- Aging political elite: The president’s advanced age and rivalry among competing inner circles place the state in “chronic waiting.” Uncertainty surrounding succession confuses governance, weakens expectations, and fuels risky political maneuvering.

3- Loss of trust between citizens and elite: Decades of corruption, concentrated power, and unfulfilled promises have deeply eroded public trust, leading citizens to believe state institutions have lost independence and serve elite interests, while living conditions deteriorate without meaningful reform, an environment that breeds alienation and frustration, thus depriving the state of popular legitimacy.

Third- Security challenges:

1- Anglophone Ccrisis and western strain: The protracted conflict in Anglophone regions drains resources and undermines stability. Security-centered approaches have failed to address root causes, while absence of political dialogue deepens social divisions and escalates violations. Without a fair and comprehensive settlement reintegrating western regions, regime legitimacy and prospects for development remain weak.

2- Boko Haram threat and northern border fragility: Boko Haram exploits porous borders and underdevelopment to expand influence in the north. Ongoing attacks exhaust the army and disrupt agriculture and trade, perpetuating poverty and recruitment cycles. Effective cross-border coordination and sustained development programs are essential to prevent the north from remaining a permanent insecurity hotspot.

3- Refugee influx and border resource strain: Growing refugee arrivals from the Central African Republic and neighboring countries aggravate competition over scarce resources and public services. Overlapping cross-border criminal activity poses serious internal security threats, particularly in vulnerable regions. Intelligent border management and support for host communities are critical to prevent this crisis from becoming a tool for political and security blackmail.

Four Scenarios for the Political Landscape

Cameroon enters a new presidential term under contested legitimacy and mounting security, economic, and political pressures. The regime’s ability to manage public anger depends on implementing tangible electoral and administrative reforms, pursuing a gradual settlement to the Anglophone crisis, and making real progress on unemployment and corruption.

Heavy reliance on security partnerships externally limits government maneuverability and raises the cost of failure. Internally, the absence of a clear succession path exacerbates institutional fragility. Consequently, the country’s future oscillates between gradual integration and prolonged paralysis and instability.

Prominent possible scenarios include:

1- Broad reforms to restore voter confidence: The regime could launch genuine reforms restoring some public trust. Measures would include enhancing electoral transparency, expanding political space, and restructuring the economy to benefit poorer segments. A comprehensive national dialogue to resolve the Anglophone crisis might be initiated. This path would enable gradual stabilization, allowing Cameroon to balance security with measured political openness.

2- Persistence of crises and decline in government popularity: Failure to translate promises into meaningful reform would confine policies to security and administrative measures, ignoring root causes of discontent. Unemployment and poverty would deepen, opposition restrictions continue, and large societal segments disengage politically. Cameroon would become a model of “enforced stability,” where power is maintained through repression rather than legitimacy, risking social upheaval.

3- Rising political tensions and alliances: Under pressure, Biya might seek alliances with moderate opposition figures or elite elements to absorb public anger and reconfigure the regime more flexibly. This scenario would grant temporary respite and restore some political balance but fail to address the crisis’s root. State institutions would remain bound by personal loyalties rather than democratic principles, making stability fragile and temporary.

4- Military coup influenced by neighboring states: Should unrest escalate and the economic crisis deepen, the military might intervene under the pretext of “saving the state,” echoing recent coups in Africa. Such a takeover would usher in a murky transitional phase oscillating between promises of salvation and risks of international isolation and internal fragmentation.

In conclusion, Cameroon appears to be entering a phase demanding a fundamental redefinition of its internal foundations before redefining its global relations. The depth of economic challenges, sharp political divisions, and persistent security tensions make continuation of traditional governance a risk extending beyond the regime itself. President Paul Biya’s ability to transform his new term into an opportunity for rescue rather than crisis extension depends on willingness to share power and free state institutions from one-party dominance. Cameroon will either regain citizen trust or remain trapped in stagnation that erodes its legitimacy and standing within Africa.

Source: Futureuae